On 28 January, the Wisbech and Fenland Museum announced that it had been awarded £616,000 in Historic England funding. This covers 90% of the costs of essential work to maintain the building’s integrity. The full cost of the renovation, including critical repairs to the roof, will be £684,000, with the museum raising the rest through a variety of initiatives.

Dominating Museum Square in the centre of town, the Wisbech and Fenland Museum building is Grade II* listed. Its roof had deteriorated to the extent that rainwater was damaging the interior, a situation exacerbated by drainage issues. The museum’s perilous structural condition earned it the dubious honour of a place on Historic England’s Heritage at Risk Register in 2018, when funds were provided for project development and emergency repairs to see it through the winter.

On the face of it though, £684,000 seems an awful lot of money to spend on a small town museum, even one as pretty as this. But to see the true significance of Wisbech and Fenland Museum means to dig a little deeper into its history and, surprisingly, that of Britain’s museums in general.

Original features

The Wisbech and Fenland Museum building dates only to 1846-47. Yet it is among the oldest purpose-built museums in the UK. Erected on part of the filled-in moat that once surrounded Wisbech’s Norman castle, the building is itself an exhibit, on a scale grand enough to house a museum collection. The lopsided windows tell a story of subsidence soon after its completion. And many of the display cases and other internal features are also original.

The building is much as it was in 1847. And that’s also true of the display cabinets, bookcases and, it’s believed, the spectacular staircase and balconies in the main gallery. Internal damage caused by water leaking through the roof has ironically revealed more original materials, including wallpaper and paint.

All of which is difficult to grasp without historical context. Queen Victoria was ten years into her 63-year reign when the museum opened and had married her beloved Albert just seven years previously. Lord John Russell, a Whig, had become prime minister in June 1846. Considerably more relevant to the everyday lives of Wisbech people, the town’s canal was thriving. The Wisbech and Upwell Tramway, which ultimately killed off most of the canal’s trade, was still 36 years off – it opened, as far as Outwell, in 1883.

Strong collection

But let’s not suggest for a moment assume that the Wisbech and Fenland Museum is stuffed with dusty exhibits of no relevance to the modern world. As with so much that we previously took for granted, the museum is closed under Covid-19 restrictions. But its small team of staff, and larger group of volunteers, is delivering an ambitious programme of online events and exhibitions.

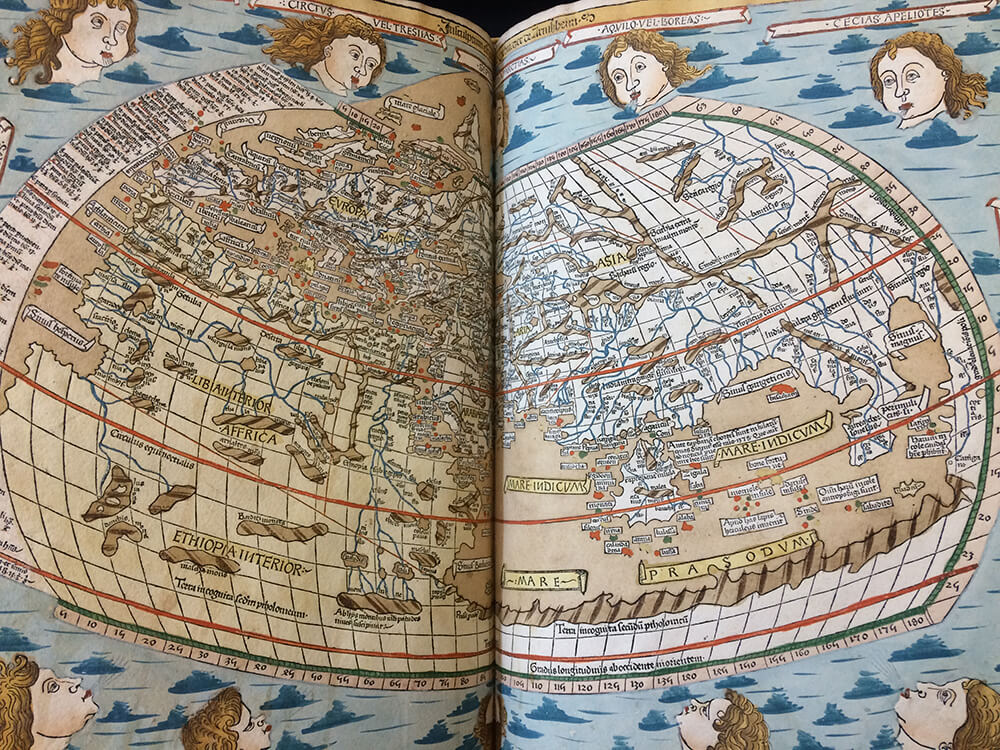

Yet the museum’s greatest strength is its varied collection. It holds a bewildering selection of local records, documents, maps and photographs, as might be expected of a town museum. It also has a surprisingly large library and an astonishing collection of historic documents.

Famous names

Many of these documents were bequeathed in 1868 by The Reverend Chauncy Hare Townshend. They famously include the original manuscript of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations, but the wider Townshend Autograph Collection includes hundreds of original pieces. These range from correspondence to individual signatures and are from a variety of historically significant personalities.

Among them, an 1850 letter from Hans Christian Anderson to Dickens is charming. But it’s difficult to choose a stand-out item from pages touched by the hands of Ludwig van Beethoven, the poet Lord Byron, Charles II, Oliver Cromwell, René Descartes, Elizabeth I, Georges III and IV, Victor Hugo, Edward Jenner, John Keats, Louis XV and XVI of France, Marie-Antoinette, Mary Queen of Scots, Napoleon Bonaparte, Horatio Nelson, Sir Robert Peel, Cardinal Richlieu, Rubens, Mary Shelley, Lord Tennyson, Queen Victoria, the Duke of Wellington and William Wordsworth, among others.

Something for everyone

Even then, the heart of the museum remains its galleries. The exhibits are truly reflective of the Victorian fascination with collecting, which means it has something to pique pretty much any interest. If Ancient Egypt is your thing, the Wisbech and Fenland Museum has something for you. You like prehistoric animals? Again, you’re covered. Minerals? Yes. Fossils? Of course. Antique weaponry? Yep. Natural history? Plenty.

In fact, if you’ve never been to a museum before, then Wisbech and Fenland Museum is the perfect introduction. It’s small enough to skim in less than an hour, sufficiently comprehensive to last all day. And if you only ever go to one museum, then Wisbech and Fenland Museum has something for everyone and everything for some. Plus, where else can you visit a museum in a museum?

WORDS Paul Eden